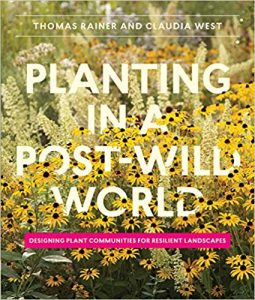

At the beginning of the week, I was in Toronto to speak at Landscape Ontario, a combination of huge trade show and several educational courses. The speaker before me on Tuesday was Thomas Rainer who authored a book with Claudia West in 2015 called Planting in a Post-Wild World. To quote the synopsis on Amazon, this is “an inspiring call to action dedicated to the idea of a new nature—a hybrid of both the wild and the cultivated—that can flourish in our cities and suburbs. This is both a post-wild manifesto and practical guide that describes how to incorporate and layer plants into plant communities to create an environment that is reflective of natural systems and thrives within our built world.”

At the beginning of the week, I was in Toronto to speak at Landscape Ontario, a combination of huge trade show and several educational courses. The speaker before me on Tuesday was Thomas Rainer who authored a book with Claudia West in 2015 called Planting in a Post-Wild World. To quote the synopsis on Amazon, this is “an inspiring call to action dedicated to the idea of a new nature—a hybrid of both the wild and the cultivated—that can flourish in our cities and suburbs. This is both a post-wild manifesto and practical guide that describes how to incorporate and layer plants into plant communities to create an environment that is reflective of natural systems and thrives within our built world.”

Panicum virgatum ‘Heavy Metal’ – narrow at the base but broader at the top ina test plot of University of Minnesota

Calamagrostis ‘Karl Foerster’ used as punctuation with red dahlias at Floriade

Geranium psilostemon as a mingler with Lilium ‘Dani Arifin’, Lupinus perennis, and Clematis ‘Reiman’ in my garden

What fascinated me about his talk was the notion that plants have varying degrees of sociability. Some plants are loners and they can often be recognized by their structure. For instance, many ornamental grasses are narrow at the base but widen as they increase in height. Needless to say, these grasses are clumpers. Plants such as these can be used in a planting design as punctuation. On the other hand, perennials such as hardy geraniums are very social. They spread by underground root systems and tend to mingle with, not overwhelm, other types of herbaceous material. Thomas pointed out that observation of these plants in their native habitats quickly identifies their level of sociability.

Monarda ‘Dark Ponticum’ and ‘On Parade’ as spreaders that are are going to need attention in my garden so they don’t take over.

Just as some people are friendly and others are not, so too can we describe plants if we have gotten to know them. Although some plants perform very well, we may not want them in our gardens. I’m talking about the bullies who want to dominate everyone else. I love the flowers of Monarda (Bee Balm) and so do the bees but putting them into a design for a perennial garden is an iffy proposition if the client wants low maintenance. Monarda spreads quickly, particularly I rich soil, and unless you have a shovel handy, it can easily take over.

Small colony of Trillium grandiflorum at base of old Magnolia soulangeana in my back garden

In plant communities, there is a sense of spontaneity and harmony that is the result of a plant establishing in a site that can support it. The irony is that what we perceive as happy, well-adjusted plants is more often the result of a scarcity of resources rather than an abundance of it. A plant’s placement on a particular site is a result of its tolerance to the environmental conditions of that site. The lesson to be learned is that soil does not necessarily need to be amended. Instead, plants can be chosen that are naturally adapted to a particular soil. For instance, Trillium thrive in rich soil and partial shade at the base of large trees in the wild. What makes the soil rich is years of fallen leaves that have decayed and become a natural mulch.

Heavily mulched bed

Sedum kamschaticum as green mulch for dry sunny area

In helping us recognize how different many of our landscapes are from those of the natural world, Thomas showed a slide of a typical residential landscape: a few conifers and shrubs and loads of shredded hardwood bark. A natural mulch is a green mulch, i.e. plants that act as a groundcover. We all know that homeowners mulch to keep weeds at bay but green mulch is more effective, more beautiful, and healthier for the environment. Weeds will always fill a bare space but most people don’t think of mulched soil as a bare space. Effectively, however, it is.

What I love about attending conferences is that I always learn something new or learn that my instincts are good but I now think differently about what I’ve been doing. What do you think about this notion of plant sociability?

0 Comments